Books which have been banned in Colombia

Translator: Sebastian Ben

Since 1988 there is an International Book Fair taking place in Bogotá: a space where it is possible to obtain thousands of volumes both in Spanish and in other languages. The city also has abundant bookshops, including second-hand ones, and there is always the chance to rely on online purchases. It was not always thus, however: chiefly due to religion, and to lesser extent the government, several publications were outright vetoed in these lands, and a Colombian title made it to the Banned Books index by the Catholic Inquisition.

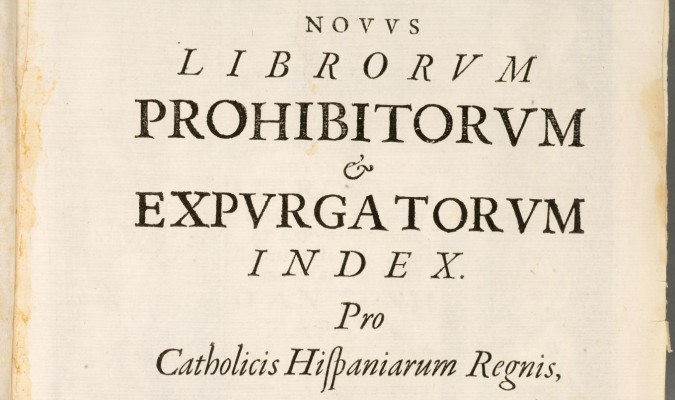

Back in colonial times, King Philip III ordered on the 25th of February 1610 for the Saint Office to be established in Cartagena. The reason why this inquisitive entity was placed outside the capital – as opposed to what had happened in the Peru and New Spain (now Mexico) Viceroyalties – was that it was meant to control the books which entered New Granada, besides being a hub for the Caribbean islands. According to ‘History of Colombia’ by Henao and Arrubla ─declared official Centenary commemorative text─ it is said that this Catholic faith preservation organism was limited ‘to watch over the non-introduction of forbidden publications.’

Illicit books were recorded in the ‘Banned Books Index’ by the Spanish Inquisition. This list was re-edited and expanded eight times over while the Cartagena Court existed. By the time the last supplement took place, in 1848, Colombia had shut the aforementioned court for just over two decades, as it had ceased in 1821 as a direct result of the independence.

Prior to that, Viceroy José Manuel de Ezpeleta, in 1794, had ordered the destruction of every single copy of the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’, translated from French and printed by ideological precursor Antonio Nariño and distributed across the streets of Santa Fe (now Bogotá).

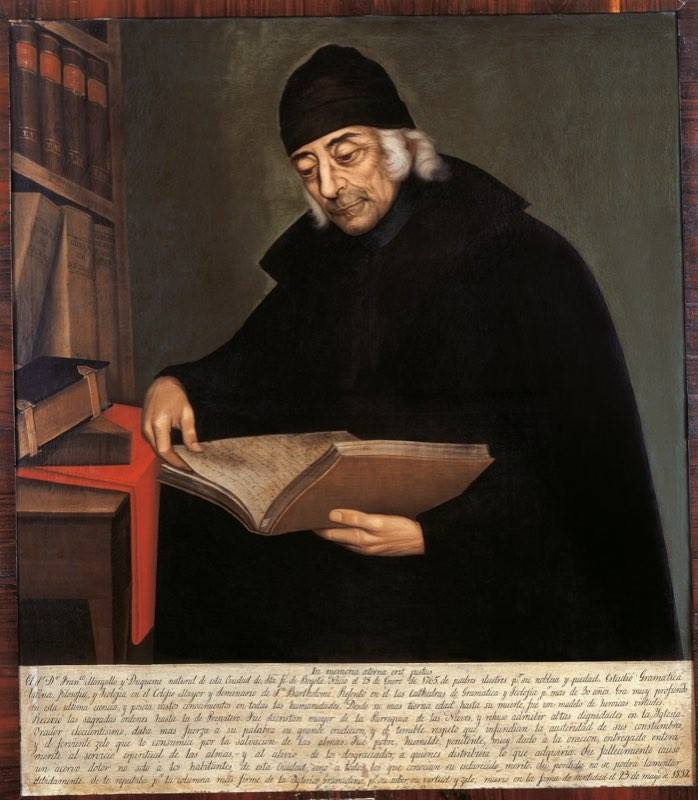

After the independence, the Catholic Church fiercely battled to keep its privileges and preclude public education, to the point of fostering armed uprising by conservatives. Padre Francisco Margallo y Duquesne preached by censoring books in Santa Fe in the early 19th century and prophesied Bogotá would be shattered by an earthquake which would take place on a 31st of August, though he refused to reveal which year.

Father Francisco Margallo was characterized by his intransigent attitude in the discussions about the principles that should guide education. He opposed the teaching of Jeremy Bentham’s theories.

Santander-born constitutionalist journalist Florentino González, who attended masses presided by Margallo, claimed he used to take note of the authors the priest slammed during the Eucharist – which included Voltaire, Rousseau, Raynal and Volney – and later on obtained them in the bootleg market, therefore becoming a remarkable liberal thinker.

During the homily, Margallo declared the Old Testament kings could have ruled wisely without ever having read ‘The Social Contract’. Every single Enlightenment work seemed to stir his inquisitive wrath: ‘Books which, favouring Epicurus over the Gospel, are going to transform the World into a theatre able to terrify the most barbarian and uncultivated Nations (…) Oh! Is here where the 18th century light is going to end up?’, the priest complained in writing.

Between 1820 and 1823 there was controversy because Saint Bartholomew School was promoting ideas by English politician and economist Jeremy Bentham. The scandal which unfolded back then could be compared to the present-day commotion stemming from gender equality and battling discrimination against LGBTI citizens, which rattles plenty of religious individuals.

See more in Daniel Coronell’s Opinion column: «La noche de la hoguera (The night of the bonfire)«

In his 1780 book, ‘An Introduction to the Principles of Moral and Legislation’, Bentham argued for a definition of utility as ‘that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness, (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered’, a principle which analysed and reformulated a number of political, social and economic aspects from that moment onwards. Bentham’s ideas were the earliest conception of State and the first form of political philosophy taught in Colombia.

Padre Margallo y Dusquene waxed lyrical against Bentham’s work claiming they had been…

‘Penned within Hell’s academy, dictated by fanaticism and rage against God and Jesus Christ’s Holy Religion, organised by ignorance and deceit, written amongst the darkness of blindness; able to foster irrational depraved education which, if it could, would constitute not a Republic as that described by Plato, but one comprising man and beast under the rule of debauchery’.

He would also turn his voice and quill against the establishment of a Biblical Society, because the Church did not want unauthorised translations to the Spanish language which lacked Catholic explanatory footnotes.

Margallo was part of a traditionalist clerical sector, initially supporting the monarchy, but which upon the creation of the Republic decided to directly oppose liberal reforms.

In 1851, the Congress of the Republic of New Granada declared that ‘1. Thoughts expressed via the press are entirely free. 2. Every substantial and adjectival law regarding thought via the press is hereby repealed,’ therefore bringing freedom of the press to our country during the José Hilario López openly liberal administration. These measures, together with the abolishment of slavery and death penalty and the expulsion of the Jesuits, led the State of Cauca conservatives to instigate a civil war.

Around 1870, a vast number of clergymen rebelled against the law establishing mandatory secular primary education. In fact, the traditionally conservative State of Antioquia never carried it out. Popayán Bishop Carlos Bermúdez even threatened parents who sent their children to public schools with excommunication because, according to him, only the Church was entitled to raise them. Public schools were, in his view, a conspiracy by Masons and liberals to corrupt the youth and expose them to forbidden volumes. Those words are reflected by contemporary Uribe-supporting Christian leaders attacks against public schools, aiming to privatise them.

The 19th century did not have a happy ending for secularism and free access to books: liberal traitor, President Rafael Núñez (better known for having penned the lyrics to the National Anthem) signed a concordat with the Church in 1888 where the Colombian government vowed to forbid school subjects to spread ideas which did not resonate with Catholic dogmata – which in practice meant vetoing Voltaire, Rosseau, Tracy, Charles Darwin, Thomas Paine, etc. Article 13 of said concordat ruled that ‘The Archbishop of Bogotá shall allocate the books which will become guidelines for morality and religion… He shall pick the texts used across public education.’ Should other ideas or books be taught or provided, ‘The aforementioned diocesan Advisor shall be entitled to remove the teachers or faculty professors from teaching those subjects.’

The first Colombian literary censorship manual arose in 1910 due to Pedro Ladrón Guevara, Spanish priest based in Bogotá, claiming in its introduction that a book would end up in that list when it was ‘Heretic, impious, sceptical, blasphemous, clergy-phobic, evil, of evil ideas, deleterious, harmful, hazardous, immoral, obscene, dishonest, lascivious, lustful, free, indecent, cynical, sultry, sensual, passionate, dangerous to youths, imprudent, reckless.’ Up to 2,057 authors were banned, including all the aforementioned ones as well as Baudelaire, Casanova, Defoe, Dumas, Isaacs, Melville, Nietzsche y Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade.

Bogotá-born liberal writer José María Vargas Vila was particularly off-putting to censors, having published most of his novels during the period of Conservative supremacy (1886 – 1930). The clergy stated his books, particularly his debut ‘Aura or the Violets’, stemmed from his atheism.

In ‘The She-Wolf Udder’, Vargas denounced the Church indoctrination:

‘Those were catechist nuns prone to teaching, mixing the most absurd fanaticism with a rudimentary barbarian pedagogy; they were one of the thousand tentacles Rome has over the cities and fields in the Americas, in order to take control of the souls and expand their immense herd of believers; sent to convert savages up the mountains, they always remain in the cities, savaging up children with the slow infiltration of the religious virus.’

With such a scathing sharp quill, censorship from the clergy was to be expected.

Also blacklisted were Bernardo Arias Trujillo, who had written ‘By the fields of Sodom: intimate confessions of a homosexual’ (1932) and General Rafael Uribe Uribe for his essay ‘Colombian liberalism is not a sin’ (1912), which had been penned as a response to ‘Liberalism is sin’ (1884) by Felix Sardá y Salvany in Spain, and which supported free speech. It was even globally censored as it was included in the Banned Books Index by the Vatican.

Many of these books could be obtained, with some difficulty, in a bookshop containing a back room, where they were concealed from public view, but they were still absent from any school library until the mid-20th century.

In many schools, including universities, even Gabriel García Márquez was banned, including his magnum opus ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ (1967), because it allegedly contained uncouth language and described sexual scenes. The veto was gradually lifted only after he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982.

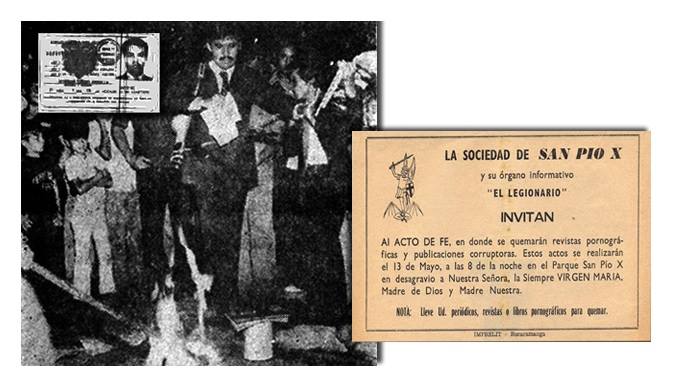

More recently, on the 13th of May 1978, day of Our Lady of Fatima, Alejandro Ordoñez Maldonado (now the Colombian Ambassador before the OAS), together with various members of the ‘Tradition, Family and Property’ organisation arranged an Inquisition-style bonfire in the city of Bucaramanga. Several books were taken out of a public library and burned, including Descartes, García Márquez, Rousseau, Freud, Marx, Mann, as well as newspapers and magazines featuring female nudity and even a Bible which they deemed erroneous for being ‘a Protestant edition’.

In 2017, Ordoñez declared on the radio that he would set books on fire again, as said act was, in his words, ‘a teaching moment’. The spirit of the Inquisition is therefore still alive in present-day public officers, many of whom would possibly censor books if they had the power to do so. Our contemporary Margallos include the aforementioned Alejandro Ordoñez as well as Marco Fidel Ramírez, Ángela Hernández and Jhon Milton Rodríguez.

After so many years of suppression, it is staggering that freedom to read has been allocated such a recent and minor percentage of time in the history of Colombia. It would be quite a good idea to be able to read the freethinking authors that the censors so eagerly wanted us not to.